In a world caught between excess and entropy, Nasreen Mohamedi’s clarity feels like resistance. Her drawings, photographs, and rare collages hold a kind of stillness that doesn’t slow time — it sharpens it. She worked with rulers and fine pens, trimming gesture down to thought. No distractions, no performance. Just structure, rhythm, and attention. That rigour is what makes her relevant now — especially for younger artists who are looking for models of discipline that don’t shout for attention.

Mohamedi’s minimalism wasn’t an aesthetic borrowed from the West. It came from her own relationship with space — Islamic architecture, Japanese design, desert light. Her grids weren’t neutral. They carried tension. Unlike Agnes Martin’s serene repetition, Mohamedi’s lines push and pull, holding friction in balance. There’s a quiet pressure in her drawings — almost like they’re thinking through the page. For artists today navigating an image-saturated world, that internal logic offers a clear counterpoint. Her work reminds them that minimal doesn’t mean empty — it means concentrated.

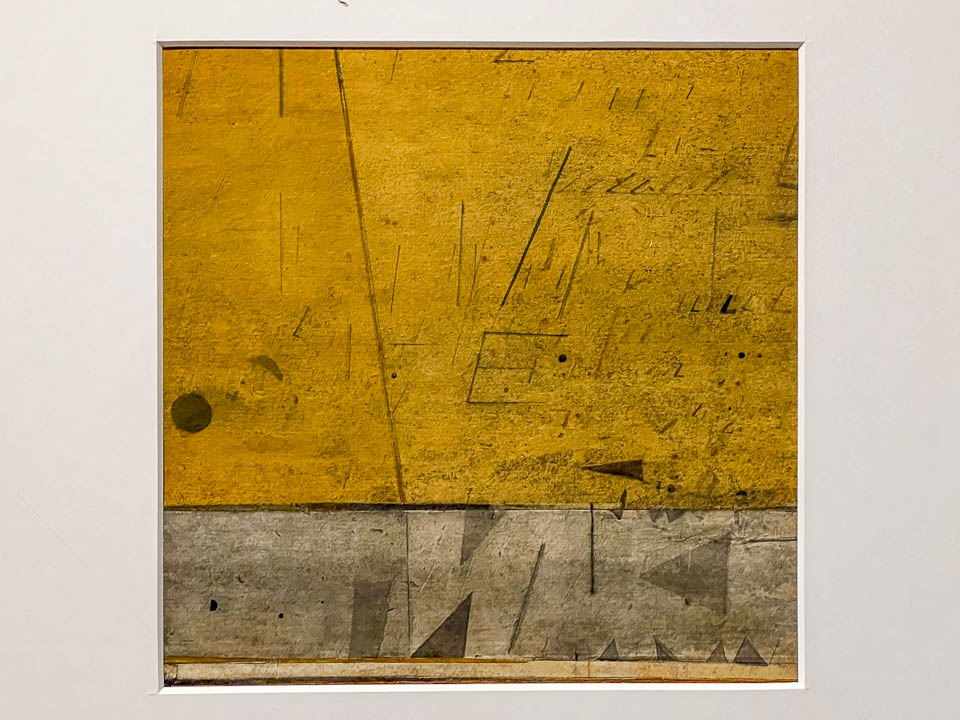

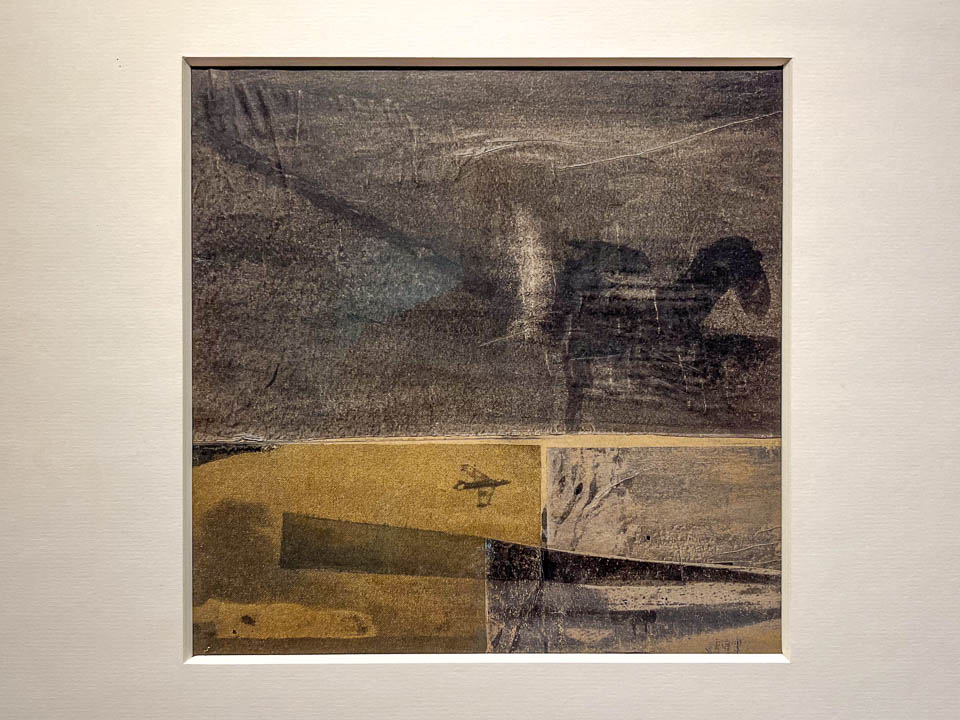

Her collage works, though less known, offer something different. Here, the line loosens slightly. She assembled textures, fragments, even text — letting abstraction take a more tactile form. They suggest a mind at work, experimenting with form without falling into formalism. In today’s language, you’d call it process-based. But she wasn’t chasing trends. The decisions were deliberate, precise, and silent. That silence now feels potent.

Collectors have started recognising this. Her works, once overlooked in the Indian market, now sit in major international collections. But the point isn’t value. It’s longevity. Mohamedi built a body of work that resists obsolescence. It doesn’t date because it never relied on fashion or identity cues. The strength lies in how it asks to be seen — not consumed.

For young artists, she sets a tough precedent. She worked slowly, without spectacle, often under physical strain. She didn’t leave manifestos, only diaries — elliptical and austere. There’s no shortcut into her work. It has to be earned. That’s the lesson: hold your line, edit harder, work like you mean it.

In the Indian context, she still feels like an outlier. She didn’t lean on myth, didn’t illustrate politics, didn’t join a movement. Yet she made some of the most consequential work of her time. And that’s what makes her vital now — not as a historical footnote, but as a reference point for how to make art that holds its own, with no explanation, and no compromise.